Potential impacts of deep seabed mining on our tuna fisheries

This article has been drawn largely from 2 reports. One was published in the journal Nature in June 2023, and the other, a Secretariat for the Pacific Community (SPC) report from 2018. These references are available on request.

Climate change is driving and increasing overlap between eastern Pacific tuna fisheries and the emerging industry of deep-sea mining. Climate models suggest that tuna distributions will shift in the coming decades. Within the Clarion-Clipperton Zone of the Pacific Ocean, a region containing 1.1 million km2 of deep-sea mining exploration contracts, the total biomass for bigeye, skipjack, and yellowfin tuna species are forecasted to increase relative to today under two tested climate-change scenarios. Percentage increases are 10–11% for bigeye, 30–31% for skipjack, and 23% for yellowfin. The interactions between mining, fish populations, and climate change are complex and unknown.

Just as there is a very real risk that deep sea mining in the CCZ could impact tuna fisheries as they move east with climate change, here in the Cook Islands we also run a risk that any deep sea mining in our Marae Moana may also impact our tuna fishery.

The 2018 paper by SPC predicted an increase in tuna catch in the Cook Islands of around 18%, as the warming seas push the tuna further to the east. This has potential significant economic benefits for the country. However, interaction of tuna stocks with the impacts of deep sea mining in our EEZ may create conditions much less favourable for an increase in tuna stocks, with the potential for conflict and resultant environmental and economic repercussions.

If any, or all, of the three deep-sea mineral companies issued with exploration licences in the Cook Islands , are permitted to move to a commercial mining phase, conflict between fisheries and deep-sea mining will likely occur. Impacts can occur from a number of pathways.

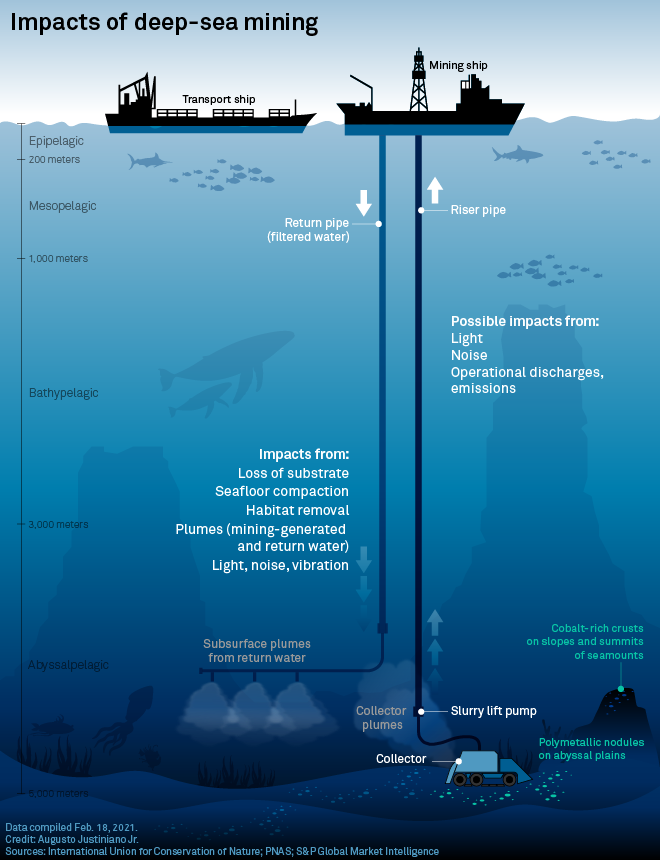

During the mining process, there will be two plumes, one where sediment is stirred up by the mining of the nodules at the seafloor, and a second where unwanted water and material separated from the nodules is discharged into the ocean from the surface mining vessel. The discharge plumes will raise the particle concentration in the water column. This could interfere with and harm filter feeding apparatuses and gills of tuna and their prey (which include marine organisms that move into much deeper waters), reduce visual communication, and increase stress hormone levels. This could extend the impacts of deep-sea mining horizontally for tens to hundreds of kilometres and vertically for hundreds to thousands of meters.

Second, the return-water discharge plume is expected to contain elevated concentrations of metals. As minerals are collected, they will likely fragment with some dissolving into seawater and some sticking to sediment or organic particles. Such particles could be ingested and incorporated into deep-sea food webs entering our seafood supply with toxins accumulating in tuna, as they are predators near the top of the food web. Even if there were only localised effects or low risks from toxic accumulation or contaminant presence, this could still have a high impact on tuna fisheries through a negative consumer/market reaction.

Third, mining noise could also be extensive and cause physiological impacts in tuna and their prey, leading them to alter their feeding and/or reproductive migrations, and potentially reducing catch rates.

At this stage, the only research being done on the potential impacts of deep seabed mining is being done by the companies intending to mine. Dr Amon, quoted in another article in Scientific American released this month, says “there's a fundamental difference between science to understand and science to exploit”—something she has learned from working in both situations. She says science to exploit often becomes “a tick box exercise”—doing only what's needed to satisfy a checklist. The problem with that, Amon says, is “not all contractors are doing high-quality science. Not all contractors are doing a lot of science. And not all contractors are making their science accessible.” Dr Malcolm Clark, a New Zealand biologist who has served as an adviser on the International Seabed Authority's Legal and Technical Commission for the past seven years, and also advises the Cook Islands Seabed Minerals Authority, agrees.

Given the many outstanding critical scientific gaps related to the impacts of deep-sea mining, fisheries, and climate change, as well as their interactions, that must be closed through scientific research for effective management to be possible, it would make sense for the Cook Islands not to permit mining unless and until the likely impacts are properly understood, and manageable within agreed thresholds including consideration of potential effects on tuna stocks. This will require a significant amount of time, with 10 years or more of comprehensive and independent scientific research.