The Matenga’s biodiversity journey in Akapuao, Titikaveka

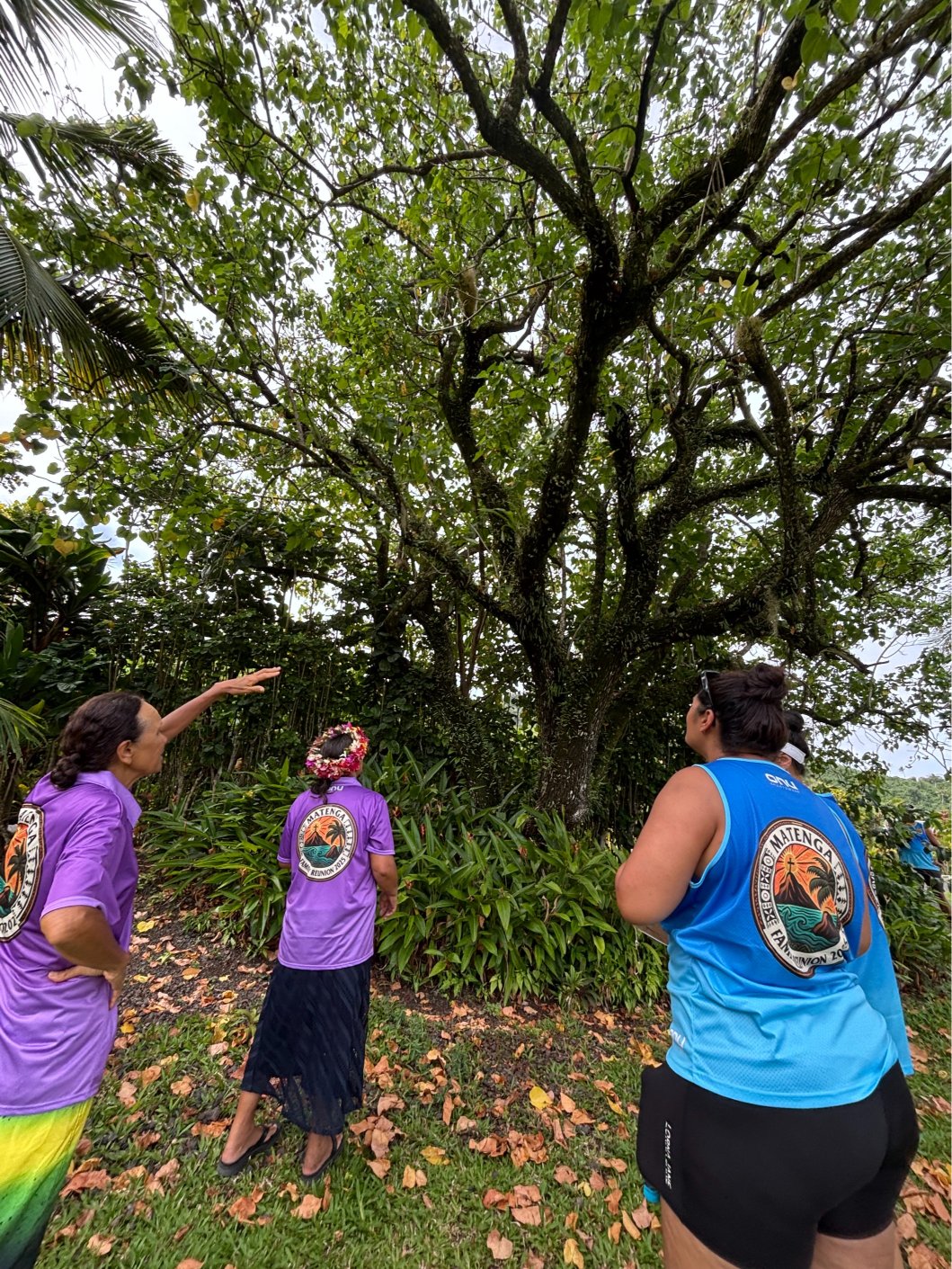

The festive season in Rarotonga has seen an influx of returning families from overseas coming together to celebrate the summer holidays and participate in a number of family reunions. One family reunion included the descendants of Papa Dr. Teariki and Jane Matenga from Akapuao, Titikaveka. This reunion not only served as a time for bonding and understanding the family’s genealogy but also featured an educational activity that allowed the family to connect with the land and its natural surroundings. The Matenga’s embarked on a walk around the village of Akapuao, aiming to identify local plants, trees, birds, and livestock by their species name, as well as by their Cook Islands Māori and English common names.

An additional component to the activity involved determining whether the species observed were native to Rarotonga or introduced by humans. This step gave the participants a chance to reflect on the rich history of the Cook Islands and its evolving relationship with the natural environment. The walk revealed that the family was quite knowledgeable about the various fruit trees and ornamental plants in the area, correctly identifying a variety of species. These included the custard apple (naponapo), pawpaw (nita), common guava (tuava), Malay apple (ka’ika), soursop (katara’apa), and mango (vi). All of these tasty fruit trees are introduced species. The only exception was the Indian mulberry (nono), which is native to the Cook Islands.

One notable observation during the walk included the breadfruit tree (kuru) which is deemed not native to the Cook Islands but was introduced some 1,500 years ago by early Polynesian settlers, as part of their voyaging and agricultural practices. Other common crops brought over during this time included taro and yams.

As the walk continued, the family encountered several streams, or kauvais, and noticed new species taking over the streams. This included introduced species like Kang kong (rukau taviri), a leafy green that can be used as a vegetable similar to spinach, and the Cape blue water lily (riri vai), both not native to the Cook Islands. By the end of the walk, it was clear that the majority of species found in Akapuao—both plants and animals—were introduced. This included fruit trees, village livestock (pigs, goats, dogs, and cats), and even the mosquito (namu), which was brought in by earlier settlers.

However, there are still some important native species to be found. The family spotted a number of seabirds, such as the white tern (kakaia) and the noddy (ngoio), which are native to the Cook Islands. They also identified native trees like the coral tree (ngatae) and the Pacific rosewood (miro), which are originally or naturally found in parts of the Cook Islands.

Understanding the role of native species in an ecosystem is crucial for maintaining an ecosystem’s health and sustainability. Native species are perfectly adapted to the local environment and therefore provide better support to local food webs and processes like pollination, nutrient cycling, and soil formation. Ecosystems rich in native species are more resilient and better able to recover from disturbances such as storms, droughts, or disease.

The walk around Akapuao highlighted the significant role introduced species have played in shaping the landscape of Rarotonga. However, it also served as a reminder of the importance of preserving native species, as they are the foundation of a healthy, resilient ecosystem. While introduced species can provide valuable resources, the balance between them and native species is essential for maintaining the ecological integrity of our islands. As the Cook Islands continue to navigate the challenges of climate change, alien invasive species and environmental preservation, understanding and protecting native species will be key to ensuring a sustainable future for both the land and its people.