We need longer term solutions to Dengue

According to the Relief Web website, as of 10th February the Cook Islands has had 614 probable, confirmed and suspected cases of dengue to date. No doubt there have been many more cases, as people with less severe cases dont bother to go see a doctor, as there is little that can be done.

Te Marae Ora’s response to date has been to spray pesticide in the areas where dengue has been reported. On Friday 13th February they also coordinated an island wide clean up in Rarotonga, Aitutaki, Atiu, Mauke and Mangaia, in the hope of removing mosquito breeding areas. From the huge amount of rubbish seen bagged up along the roadside, this was a well supported and successful initiative.

The main dengue carrying mosquitoes are highly adapted to human environments, preferring to rest indoors in dark corners, under furniture, or behind curtains where street-side sprays rarely reach. A potential problem is, over time, heavy use of these chemicals has likely allowed mosquito populations to develop resistance to common insecticides, rendering the spraying less effective.

Perhaps the most significant risk of broad-scale spraying, especially on an island, is the collateral damage to "non-target" species. Islands are delicate ecosystems where beneficial insects play important roles in maintaining local flora and food security. When a truck sprays a broad-spectrum insecticide, the chemical does not discriminate between a disease-carrying mosquito and a vital pollinator. Native bees and butterflies can be caught in the crossfire. Te Marae Ora does try to limit the impact by spraying when the bees are less active. However, if these populations are effected, the island’s fruit production and native plant reproduction can suffer significantly.

Further impacts can occur through killing off the predators, such as dragonflies, that naturally keep mosquito numbers in check. This can result in a rebound effect where the mosquito population returns even faster because their natural enemies have been wiped out by the same spray.

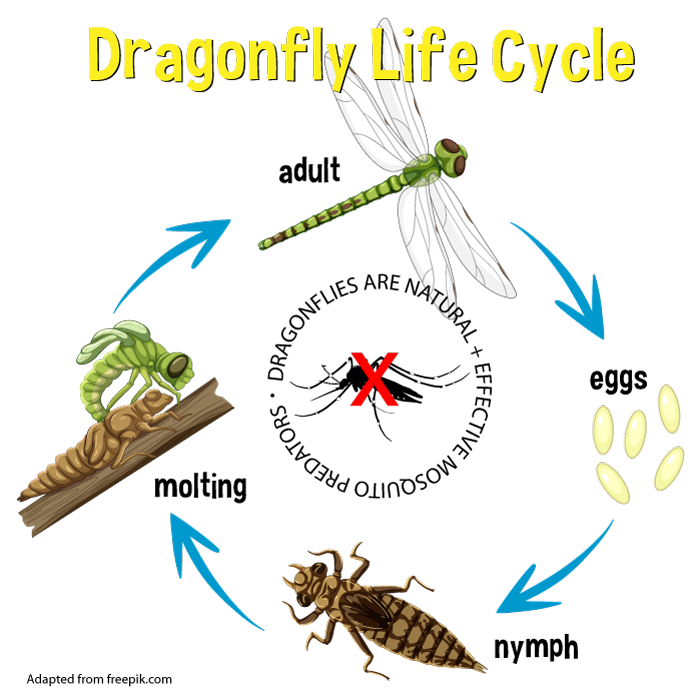

A longer term approach to solving the problem involves using natural control methods. Nature has spent millions of years perfecting mosquito predators, with dragonflies serving as the undisputed winners in the fight against mosquitos. Dragonflies are lethal at every stage of their life cycle. As aquatic nymphs, they live underwater for months or even years, consuming mosquito larvae before they ever have the chance to fly. Once they reach adulthood, they utilise specialised vision and high-speed maneuverability to catch adult mosquitoes mid-air. Supporting these predators can create a self-regulating ecosystem that does not require chemicals.

The true long term solution to the Dengue problem lies in Integrated Pest Management, which shifts the focus from "killing bugs" to "managing environments." While localised spraying may be necessary during a sudden, severe outbreak to provide a quick knockdown of the adult population, it is a short-term tactic rather than a long-term strategy. The real victory is won through source reduction—physically removing standing water in gutters, tires, flowerpots and plants holding water. For example, Bromeliads central "cups" are perfect nurseries for mosquito larvae. A quick tip is to flush them out with a hose once a week or tip them over after a rain. You can also plant vegetation around your house that discourages mosquitoes, like lemongrass and basil.

We should also foster a landscape where natural predators like dragonflies can flourish. By protecting our wetlands and reducing our reliance on broad-spectrum chemicals that threaten pollinators and endemic species, we allow the ecosystem to do the work for us. In the end, a healthy population of dragonflies and a community committed to regularly emptying their containers containg water are far more effective at stopping Dengue than a pesticide truck passing by once an outbreak has started.

To encourage dragonflies without breeding mosquitoes, you can build a pond with circulating water or introduce mosquitofish found in our streams (Gambusia affinis) to consume any developing larvae. Placing sunning sticks (perches) provides essential vantage points for these aerial hunters. This creates a "guarded" habitat where dragonflies thrive, but mosquitoes cannot survive the constant predation and water movement.

By shifting our focus from temporary chemical fixes to these long-term biological solutions, we do more than just lower the risk of dengue. We transform our surroundings into self-sustaining mini-ecosystems. When we invite nature’s most efficient predators back into our gardens, we aren't just fighting an insect—we’re restoring a balance that keeps our communities healthier and our environment more resilient for years to come.