Why we need a mining moratorium

The deep sea is sometimes viewed as a barren wasteland. However, a recent discovery, the production of ‘dark oxygen’, is challenging this outdated idea and raising critical questions about the rush to begin deep-seabed mining (DSM).

In a recent article in the Cook Islands News, Gerald McCormack of the Natural Heritage Trust correctly pointed out that the deep seabed in the Cook Islands already has a relatively high level of oxygen. This oxygen travels thousands of kilometres using Antarctic currents. Based on this, he suggests that the small amount of “dark oxygen” that may be created by seabed nodules is insignificant.

However, this argument misses the bigger picture. The discovery of “dark oxygen” isn’t only about the quantity of oxygen produced; it also reminds us of the vast knowledge gap surrounding our deep ocean

To produce this dark oxygen, one theory is that the polymetallic nodules must split water molecules through a natural process of electrolysis. When water (H2O) is split, it creates both oxygen and hydrogen. This is crucial because while the oxygen may be plentiful, the deep sea is often described as a “food desert”, with very little nutrition in the form of organic matter, or “marine snow”, raining down from the surface. But could there be another food source from the seabed itself?

Hydrogen is a powerful fuel for chemosynthesis, a process where microbes use chemical energy to create food, much like plants use sunlight. In the Clarion-Clipperton Zone (CCZ), another area with abundant nodules, scientists have found exceptionally high rates of chemosynthesis, up to 44 times more than expected (Sweetman eta al, 2018). At the time, they couldn’t explain this phenomenon, but the discovery of hydrogen production around nodules provides a possible answer. This hydrogen may be fueling the microbes, which then become a food source for other animals in the deep sea. This supports the argument that the nodules are not just mineral deposits; they may be foundational pillars of a unique food web in an otherwise resource-poor environment.

The term “biological desert” is often used by supporters of deep seabed mining to imply that the deep seabed is an empty, unimportant place that doesn’t need to be protected. This is an unfortunate misconception. There are other ecosystems, with relatively low biomass, which are very important to our life on Earth. They are full of unique, highly-adapted species and provide vital ecosystem services. The surface of the arctic ice shelf is a low biomass system yet is critical for climate regulation as it reflects sun energy back to space. The Galápagos Islands are a low biomass ecosystem. Had we destroyed it before Darwin came along, we may have never thought about evolution or discovered many of the medical marvels that were grounded in this theory and the world would have been a sicker place.

Deep-sea “deserts” if you want to label them as that, offer similar opportunities. For example, they play a key role in global processes like carbon storage and climate regulation, absorbing carbon from the atmosphere and storing it in the seafloor.

These areas are home to a myriad of unique species, most of which we haven’t even discovered or described. We have seen from land-based deserts that their specialised, endemic species are often the first to face extinction when their habitats are disturbed. The same will undoubtedly be true for the fragile, slow-growing life on the deep seabed.

The discovery of “dark oxygen” is a powerful wake-up call. It highlights how little we know about what happens on our own seabed and reveals a hidden complexity of the deep sea ecosystem that could be irreversibly damaged.

The bottom line is simple: we cannot risk destroying a potentially life-sustaining ecosystem that we do not yet understand. The discovery of dark oxygen, and potentially the hydrogen produced alongside it, strengthens the call for a complete moratorium on deep-seabed mining. We need much more time for research to uncover the secrets of the deep before any decision is made to destroy vast areas of this unique and precious environment. (References available)

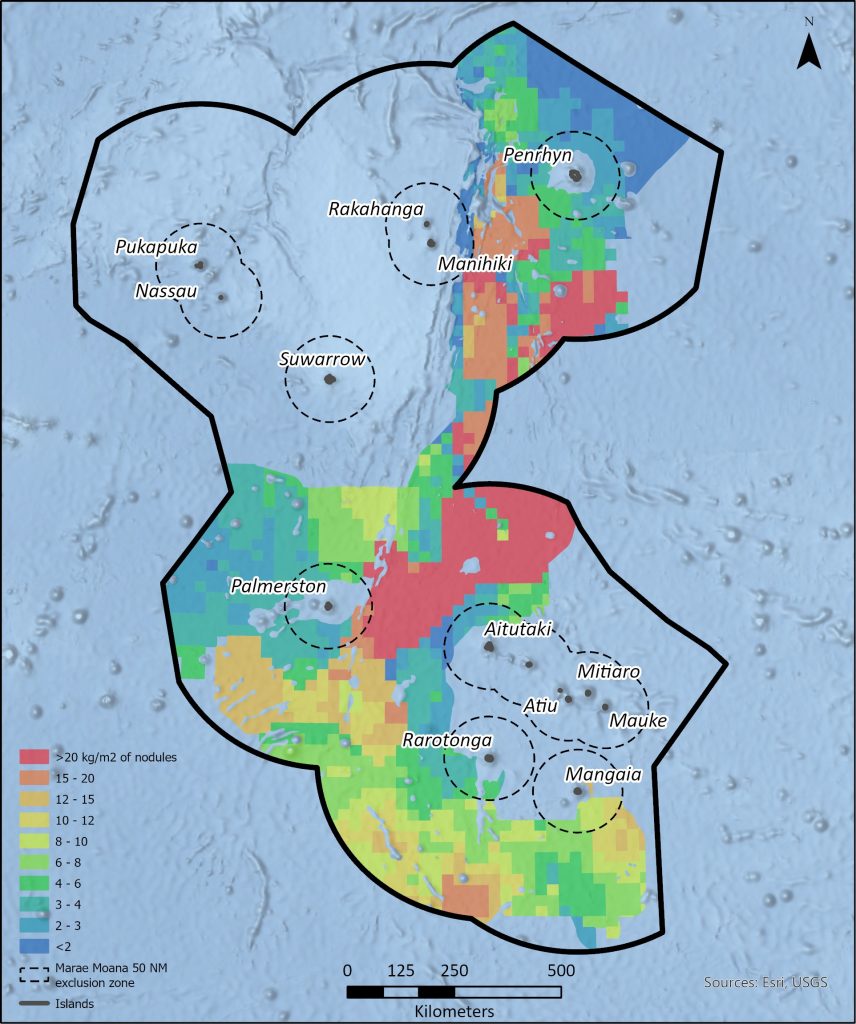

The map below, from the Cook Islands Seabed Minerals Authority (SBMA), shows estimated nodule abundance (kg/m2) in explored parts of the abyssal plains within the Cook Islands exclusive economic zone (EEZ).