A contradiction in practice?

The phrase sustainable development suggests sensible progress — meeting today’s needs without harming the ability of future generations to meet theirs. This idea, made popular by the 1987 Brundtland Report (Our Common Future), aimed to reshape global growth. Its rule was simple: if you take sand from the beach for concrete to build a home today, you must ensure there is still sand and a stable beach for your grandchildren to do the same tomorrow. It was a vision that balanced economic growth with environmental care, calling for long-term ecological thinking.

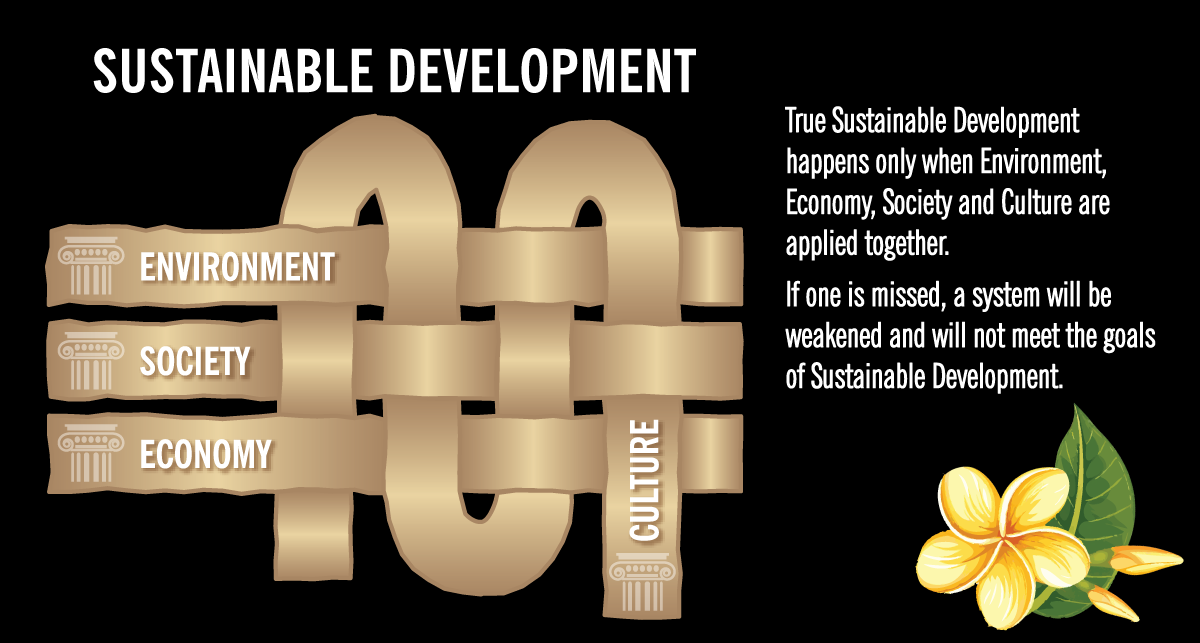

Since the concept’s adoption by the United Nations, the meaning of ‘sustainable’ has shifted. The original model rested on three pillars—economic viability, social equity, and environmental protection. The social pillar focussed on aspects like community well-being, poverty, equity, and education. But for many communities a distinct fourth pillar—Culture—was needed to ensure development respects local heritage and identity. However, today the term ‘sustainable’ is often used by corporations and governments to describe actions that are merely financially sustainable or have long-term profitability.

This shift lets companies label lucrative or technologically advanced—but environmentally harmful—activities as sustainable. By defining polluting or extractive practices as ‘sustainable’ through carbon offsets or appeals to global necessity, the original intent of Sustainable Development is diluted, reducing a moral safeguard to a marketing term.

A stark example of this conflict is the growing push for Deep-Seabed Mining (DSM). Proponents claim that extracting nodules from the seabed — rich in cobalt and nickel — is essential for the green transition, making DSM appear aligned with sustainability goals.

Whether you agree with that or not, judged by the original environmental principles, DSM still fails completely. Deep sea ecosystems are among the least explored on Earth, hosting life that grows slowly and is highly fragile. The nodules targeted for mining take millions of years to form—meaning they cannot be replenished on any human timescale. Mining them will inevitably destroy habitats we barely understand. Calling this ‘sustainable’ disregards the core idea of preserving natural resources for future generations.

The debate over DSM highlights a clear divide:

- The original principle: Progress should meet the needs of all generations by balancing resource use and renewal.

- The current practice by many governments/developers: Activities are ‘sustainable’ if they meet present financial or energy goals, even when the natural resources used cannot regenerate.

When destructive activities are labelled ‘sustainable,’ the term becomes a sales tool rather than an ethical guide. This change weakens public trust and allows decision-makers to justify quick profits without thinking about long-term harm. The focus moves from protecting the future to protecting business. In effect, ‘future generations’ then means the next few years of profit, rather than the far future of a nation’s citizens.

If sustainable development is to remain meaningful, we must return to its core principles. Sustainability cannot be a trade-off between economic need and ecological integrity; it must integrate all pillars.

A truly sustainable activity must not consume resources that cannot recover within a reasonable time. It requires honest evaluation of environmental impacts and a willingness to pause or slow projects that endanger natural systems, no matter how profitable they appear. In the case of DSM, this means a pause or moratorium until sufficient resources have been committed to unbiased research so we can grasp the ecological risks and impacts.